„In a world where technology is changing so rapidly, today’s high-tech, sophisticated global leader may be redundant in a year or two.” John McCarthy, Chief Economist, Department of Finance, Ireland

The fallout from the financial crisis silenced the roars of Ireland’s 'Celtic Tiger’ economy. Now that it’s back, its growth — and its growing pains — offer useful lessons for other small, fast-developing nations. At the Global Government Finance Summit, John McCarthy, chief economist of its finance department, described the country’s 'peculiar economy’.

„Sustainable growth and new digital technologies can be absolute game-changers,” said Noureddine Bensouda, Treasurer General of the Kingdom of Morocco. „On the one hand, they offer vast opportunities for positive transformation of economies and societies; on the other hand, they change faster than our ability to adapt and can perpetuate existing inequalities.

Introducing 2023 Global Government Finance Summit – at the annual meeting of finance sector and treasury leaders, hosted this year by the Moroccan government in Rabat – Bensouda pointed to an „increasingly complex, diverse and interconnected” set of global challenges. Civil service finance leaders play a key role in preparing their countries to survive and thrive, he said: “We must ask ourselves how public finance can adapt to this new era: governments and financial institutions must adapt their approaches, but harness the potential of digitalisation and sustainability.

During the four day-long sessions of the summit, civil service chiefs – who’s who People from 12 countries A wide range of debates will explore these issues – across five continents. But John McCarthy, chief economist at Ireland’s Department of Finance, described his country as a „strange economy”. Small, open and radically transformed over the past 20 years, Ireland illustrates both today’s many opportunities and its many risks – becoming a canary in the economic minefield.

From agriculture to medicine

McCarthy said that since Ireland joined the European Economic Community half a century ago, agriculture’s contribution to GDP had fallen from 15% to just 1%; The proportion of land-based workers has meanwhile fallen from 25% to 5%. However, unlike many countries in the developed world, Ireland has seen a rise in productivity: industrial employment may have fallen from 30% to 20% of the workforce, but its contribution to GDP has risen from 35% to 40%.

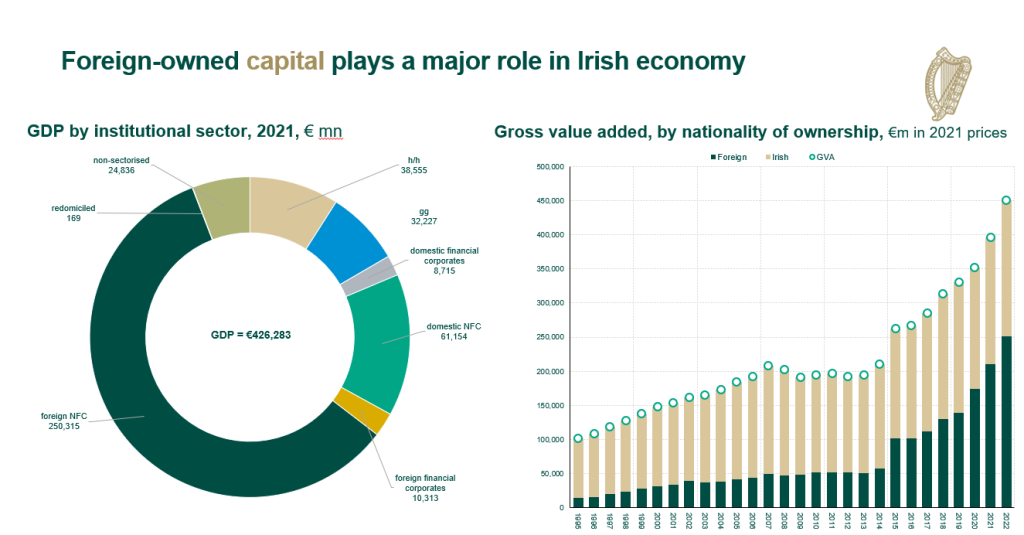

„Stuck in the mid-Atlantic, with a very small domestic market, we cannot have a comparative advantage in heavy manufacturing,” he explained, „so for 50 years, the authorities have been targeting sectors with high value-added exports, but low body weight. The country has attracted huge foreign investment, especially By pharmaceuticals and IT companies: The proportion of GDP generated by foreign businesses has grown from 20% to more than 50% over the past 25 years.

Ireland’s generous corporate tax regime is helpful here – although McCarthy has argued that its effective taxation rate is close to that of its rivals (see our forthcoming report on the summit’s taxation session). But equally important is its increasingly highly educated population: following a rapid expansion in higher education, more than half of 25-year-olds now have a degree. „We’re seeing an increase in human capital through labor,” he explained. „It was able to shift the labor market away from low-value-added and agricultural.”

Focusing hard

However, Ireland’s growth model is not without its risks. With „a small number of sectors and concentrated economic activity within a small number of companies”, the country is heavily dependent on a few large investors: half a dozen companies export most of Ireland’s goods. Corporate tax revenue may have risen from €4bn (US$4.3bn) to €24bn (US$25.5bn) in a decade, but „most of it is down to 10 companies”, McCarthy said. He knows how quickly large corporates can rise.

“At its peak, Nokia was like 3% of Finland’s GDP; I don’t know anyone who owns a Nokia phone right now. In a world where technology is changing so rapidly, today’s high-tech, sophisticated world leader may be redundant in a year or two.

Asked if the government was trying to broaden its economic base, McCarthy replied, „As a small economy, we can’t diversify that much: we have to build comparative advantage in a relatively small number of sectors.” Nevertheless, civil servants are trying to create links between the foreign-owned sector and Irish SMEs, embedding multinationals deeper into the Irish economy – offering R&D tax credits, for example – in an attempt to capture their wider territory. activities.

Meanwhile, within government McCarthy and his colleagues are „trying to reduce the risk of what we see as windfall revenue gains to fund perpetual fiscal commitments – spending increases or tax cuts”. Taxes paid by major foreign investors could be paid into a sovereign wealth fund – creating a nest egg for future generations of Irish people, while avoiding structural dependence on revenue streams vulnerable to changes in technologies and markets.

Too many jobs, not enough housing

Along with inward investment and education, Ireland owes some of its economic success to rapid immigration: the proportion of foreign-born workers has risen from 5% to 20% since 2000. Despite this credit, the rapid post-pandemic recovery — which has seen employment levels 10% higher than their pre-pandemic peak — has pushed unemployment rates down to unprecedented levels. „By any reasonable definition, we’re full of work,” McCarthy said.

In part, Ireland – unlike countries such as the UK and US, which experienced a 'great exodus’ in the wake of the pandemic – has seen rising labor market participation rates. There is little hard data to explain this difference, McCarthy said; But Ireland’s relatively young population may be less affected by the lingering effects of COVID, while rates of remote working have soared since the pandemic – rising 15 points to a third of the workforce. Changing attitudes toward flexible and remote work, McCarthy speculates, may allow more women to return to the workforce after having children.

McCarthy concluded that rapid changes in Ireland’s economy had „transformed living standards over the past two decades” – but the country now faced four slow-moving but inevitable challenges, which he summarized as the „four Ds”. Along with decarbonization and digitalization (covered in upcoming reports on the summit’s sustainability and data sessions), demographic issues and globalization represent significant threats to future growth.

Demographically, the country is not building enough houses to meet the demand created by rapid immigration. The population rose 8% in six years, but housebuilding never recovered after Ireland’s 2008 housing crash: „A lot of construction workers went out of the market and they never came back,” explained McCarthy, adding that the planning system is another barrier to construction.

After halving between 2008 and 2012, house prices returned to their 2008 peak in 2021 – fueling new social tensions. „There was no problem with immigration until about five years ago, when some of the restrictions on the housing market really started to become more binding,” he said. „But now some motivation is starting to emerge from smaller segments of the population.”

Releasing choke points

However, without continued immigration, Ireland may struggle to support a rapidly aging population: the ratio of working people to retirees is expected to fall from 4:1 to 3:1 over the next 12 years, and decline exponentially thereafter. „Population-sensitive costs will increase very, very quickly,” McCarthy warned. „Between 2020 and 2030, we need to pay an extra 3% of national income each year to maintain the current level of spending on pensions and public services.

Finally, global deglobalization indicators track an uncomfortable trend for trade-based economies like Ireland’s. It’s not yet clear that the long shift toward more integrated global supply chains has actually reversed, McCarthy said; But the pandemic and the war in Ukraine have certainly exposed „choke points: single points of failure,” which „illustrates the need to improve security of supply. Because Ireland is so integrated into global value chains, it’s something we’re thinking about a lot.

In short, McCarthy identified Ireland’s strengths as its openness – for goods, services, capital and labor – and ease of doing business: „Red tape is relatively low in Ireland,” he said. On the weaknesses side, he noted poor productivity in some public services, dependence on carbon-intensive energy sources, infrastructure gaps and low productivity in domestic businesses.

Naming the country’s economic opportunities, he singled out energy – Ireland excels in harnessing wind and wave power – and the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) initiative, which he believes will strengthen „tax certainty”. Returning to threats, he added a fifth 'D’: dependence on a handful of global firms, and UK markets – newly hampered by Brexit frictions – a target for more traditional exports such as food.

All of these issues will be at the center of finance chiefs’ discussions the following day. Includes sessions Sustainable development, data and digitization, tax reform and the role of the state as buyer and commissioner. As Bensouda put it, financial sectors have a responsibility to “accelerate the pace towards a sustainable and equitable world that leaves no one behind” – reshaping economies and retooling the workforce for the challenges ahead. „Words are important, but so are our commitments and the duty of all of us to speak up in implementing them,” Pensouda concluded. The Global Government Finance Summit will explore exactly what that means for this generation of finance leaders – and the next.

First report on this Global Government Finance Summit Held in Rabat, Morocco in June 2023, Irish Finance Chief Economist John McCarthy included an analysis of his country’s economic strengths and weaknesses. Further reports will be posted here soon.

To ensure Summit participants can speak freely, we grant everyone quoted the right to anonymize, edit, or delete their comments before publication.

„Oddany rozwiązywacz problemów. Przyjazny hipsterom praktykant bekonu. Miłośnik kawy. Nieuleczalny introwertyk. Student.