• Physics 16, 96

A technique combining X-ray spectroscopy with scanning tunneling microscopy has provided X-ray spectra of single atoms.

X-ray spectroscopy provides elegant tools to study the composition and structure of samples relevant to biology, chemistry, environmental studies, and materials science. Not only can it examine the „fingerprints” of specific chemical elements in a sample, but it can also reveal a wealth of information about the chemical states and structural organization of the atoms in the sample. Until now, however, experiments required thousands of atoms — or attograms of a sample — to get a clean enough signal. Now a team led by Saw-Wai Hla of Ohio University and Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois has, for the first time, been able to measure the X-ray spectra of single atoms. [1]. The breakthrough was achieved with a technique that combined X-ray spectroscopy with the pioneering single-atom-resolving technique of scanning tunneling microscopy (STM).

Developed in 1981, STM has acclimated us to remarkable views of the microscopic world. A decade ago, IBM researchers realized the world’s „smallest” movie. A boy and his atom, whose frames are composed of molecules moved along the STM tip. However, STM does not provide information on atomic species. „I usually image and manipulate atoms with STM. But with STM alone I can’t identify what kind of atoms are in an unknown sample,” says Hla.

The tunneling current measured with the STM tip involves electrons that are easy to remove from an atom—its outer electrons, whose features are not element specific. X-ray spectroscopy, on the other hand, targets the core electrons of an atom, which can provide unique fingerprints in the form of element-specific absorption lines. What’s more, the details of these absorption lines can reveal information about the chemical state of the atom, including how it shares electrons with its neighbors. However, the X-ray absorption of a single atom is so weak that several atoms are usually required to produce a measurable signal in a single detector.

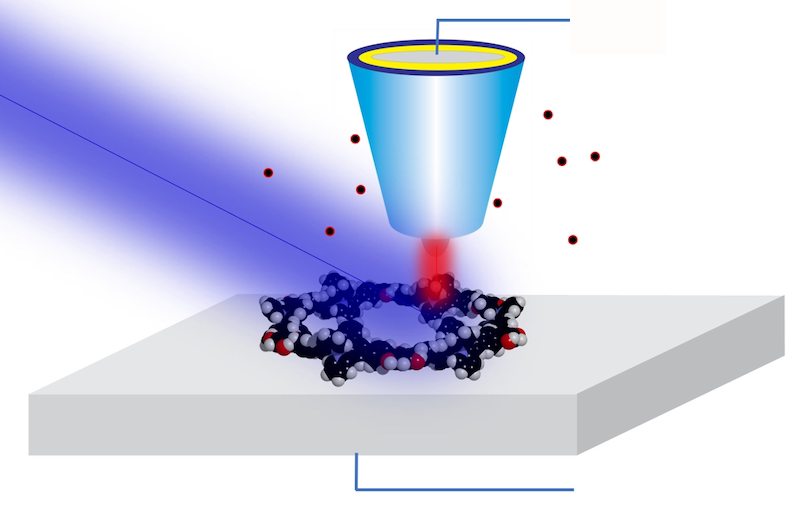

For years, Hla and his team have worked to combine the best of both worlds—the atomic resolution of STM and the chemical sensitivity of x-ray spectroscopy. Their approach uses a previously proven technique called synchrotron X-ray STM (SX-STM). In the technique, a sample is scanned by an STM probe while exposed to an X-ray beam delivered by a synchrotron. The probe records a large tunneling current when the X-ray energy resonates with core state changes in the sample’s atoms. By measuring the current as the X-ray energy varies, the researchers can recover the X-ray absorption spectrum of the sample below the tip.

SX-STM has been used for nanoscale imaging since 2009 [2], Hla says, nothing is straightforward about bringing resolution down to single atoms. A key challenge was to prepare a suitable model that could isolate a particular atom from its environment and measure it reliably. To do so, the team synthesized special supramolecular complexes—ones that allowed an atom to be placed in a controlled and reproducible state.

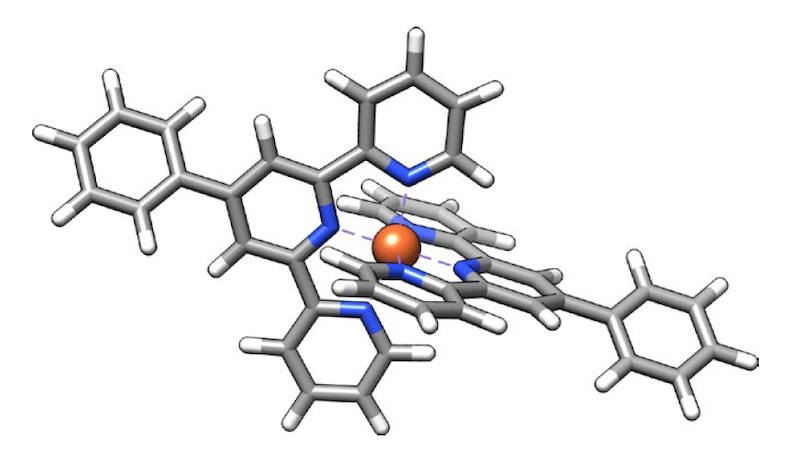

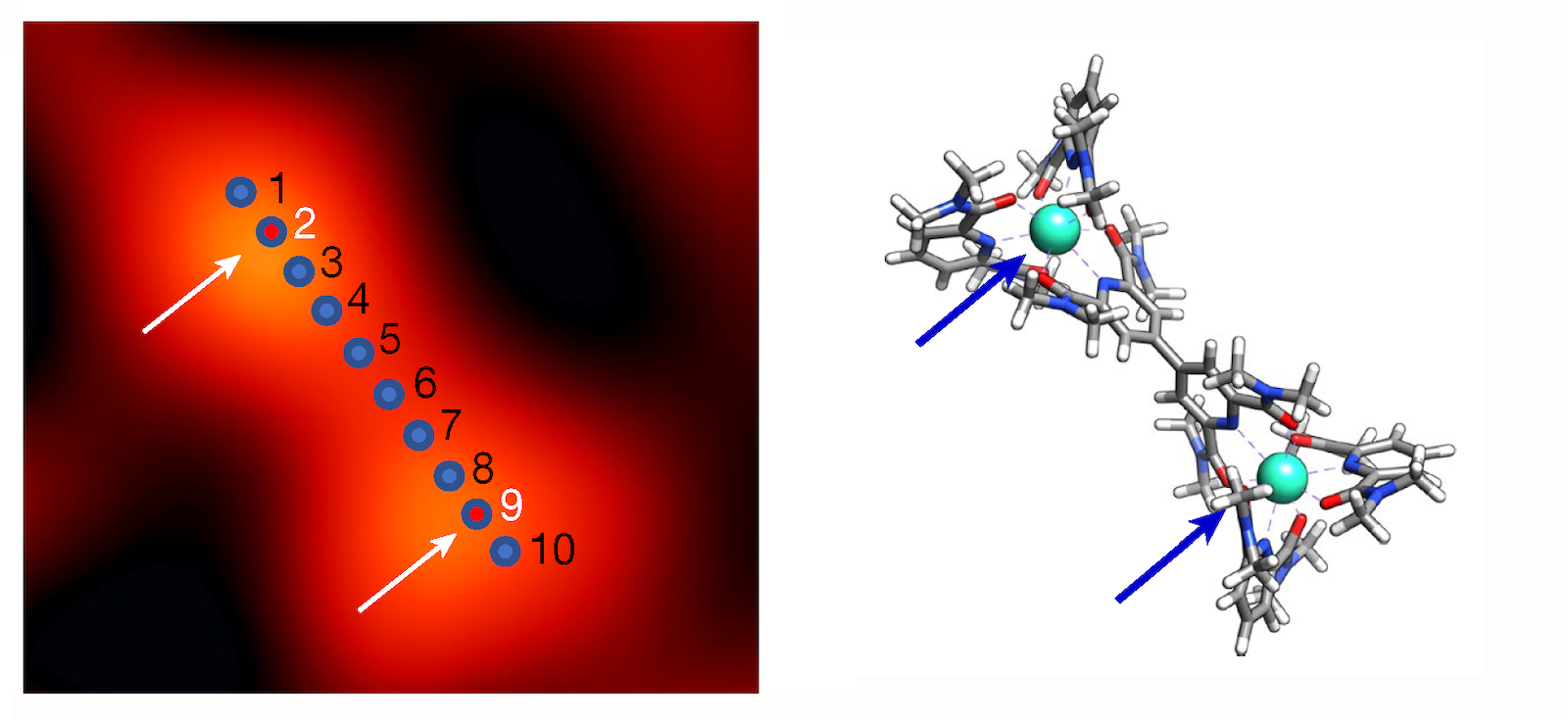

In the new work, the team examined two different elements, iron and terbium, each of which was placed in a supramolecular complex that isolated target atoms from other atoms of the same species. This design ensured that the measured tip current could be unambiguously attributed to an atom. For example, when scanning a complex of two terbium atoms tip-toe along their length, the researchers recorded terbium’s “X-ray spectra.M edge” (which involves transitions of core electrons from 3E Up to 4f in states). In a second experiment on another supramolecular complex, they found that iron „L Margin” (which includes 2p-to-3E changes) at points within the iron-bearing complex.

Beyond identifying iron and terbium atoms in the samples, the results also demonstrated the ability to reveal subtle chemical details. For example, analysis of the spectrum confirmed that iron is in the +2 oxidation state and that it interacts strongly with its surroundings (technically, the atom’s E Orbitals mix, or hybridize p orbitals of six neighboring nitrogen atoms). In the case of terbium, the team confirmed the expected property – isolation from its surroundings due to its lack of hybridization. f orbits. This weak link is important for many technological applications of terbium and other rare earths.

„It’s so unusual to do X-ray spectroscopy on an atom that it’s surprising to be able to make such a measurement so accurately. Tour de force,” says condensed matter physicist Michael Cromie of the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the study. „Sensitivity to atoms a few angstroms apart has been demonstrated,” says Thomas Jung, an experimental physicist at the Paul Scherer Institute in Switzerland. Such single-atom resolving power can help us understand and design so-called metal-organic coordination networks — promising materials for applications ranging from surface catalysis to quantum technologies, he says.

Hla says he is working on further improving his team structure. Specifically, the researchers aim to make measurements using polarized x-rays. This approach will make the experiment sensitive to the spin state of an atom, which will be invaluable for studying rare-earth-based materials with promising applications in spintronics and magnetic memory technology.

Matteo Rini

Matteo Rini Editor Journal of Physics.

Notes

- TM Ajay and many others.“Characterization of single atoms using synchrotron X-rays”. Nature 61869 (2023).

- D. Okuda and many others.„Nanoscale chemical imaging by scanning tunneling microscopy assisted by synchrotron radiation”. Physic Rev. Lieut. 102105503 (2009).

„Oddany rozwiązywacz problemów. Przyjazny hipsterom praktykant bekonu. Miłośnik kawy. Nieuleczalny introwertyk. Student.