In the seventies and most of the eighties, a group of architects, mainly British, sought to elucidate in their constructions the idea that progress was the real driving force behind the evolution of their discipline from the mid-nineteenth century. Technology: they preserved an architecture flexible in its applications, made with highly advanced materials (synthetics) and techniques derived from industries such as naval or aerospace; Its formal image should, essentially, be an image of those technologies.

At first, these postulates could only be applied to industrial constructions, but they have become widespread since 1971, following the victory of two almost unknown young people in the Pompidou competition in Paris: Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, who were responsible for the design. The center has a technical and playful proposal inspired by the work of Archigram, born from research through disposable media, space capsules, behind the imaginative projects of a heroic, pro-consumer and futuristic residential communities. Mass consumption images and clip-on technology.

Opened in 1977 (and closed for a few years for renovations), the building was met with serious controversy due to the exhibition of its technical elements (structure and facilities). Historic surroundings. However, over the years, it has become another Parisian monument, leading and High technology.

Its story is known: President Georges Pompidou wanted to go down in history by leaving behind a large monument in the heart of the French capital and promoted a call for competition to build a cultural center in the Marais; It includes the Museum of Modern Art, a library, the Institute for Music and Acoustic Studies, and an industrial design center, as well as annexes, restaurants, a cinema, etc. Engineering firm Ove Arup & Partners convinced Piano and Rogers to apply, and they were unexpectedly selected by a jury consisting of Oscar Niemeyer, Jean Prouv and Philip Johnson.

His plan included leaving half of the available space (called the Plateau Beaubourg) free as a forum for outdoor activities, leaving the entire institution open and freely accessible to all. Externally, its building looks like a huge hangar with six exaggerated open floors that can be distributed according to the needs of each moment, thus bringing into practice the desire for flexibility. The formal composition does not obey autonomous guidelines, but is the result of the complex's functional concept: a parallelism of interior spaces served from two longitudinal facades by circulation elements and amenities.

The structure of the Pompidou consisted of large cross porticoes like the Meccano and triangular beams fifty meters long resting on a kind of levers on the outer pillars and stabilized by a mesh of braces. On the main facade, an escalator encased in a glass tube from the street, from floor to floor, is the nerve center of the building's circulation, while the rear facade of the center is lined with colored pipes that match all kinds of building amenities; These contrast very clearly with the surroundings of nineteenth-century houses in this part of Paris. As for the lateral sides, they allow you to visualize the structure's outline and the entire section. The impression of 1977 was profound: one of the most important museums in France was, in fact, like a purgatory.

However, Pompidou ended the piano + Rogers studio: the first he retired to Genoa, where he was born, and the second he decided to devote himself to teaching until the construction of two industrial buildings where he would launch his new typography. profession; In the first half of the eighties, we refer to the INMOS factory and the PA Technologies laboratories. Lloyd's headquarters in London (1978-1986) though it was a hallowed job.

In that period, in the late seventies and early eighties, a way of doing architecture was integrated, in general, it was suitable for the formal envelope, including many references to the architectural styles of the past: first, and above all, the classic and the beginning of any historical phase, in the practice of radical eclecticism. This architecture, which we might call cosmetic, coincided in the United States and Great Britain with the trend of decorating facades recognizable by their shape and color, such as the packaging of consumer goods.

From a more cultural and less consumerist approach, this postmodern style became popular in Europe, with the 1980 Venice Biennale dedicated to the „existence of the past”. There, A last street Designed by Paolo Portoghesi, it featured a series of illuminated facades by Gehry, Graves, Moore, Stern, Isozaki, Hollein, Bofill, Rem Koolhaas.

Perhaps we owe the European building that best represents this eclecticism to James Stirling, whose industrial crisis of the mid-seventies made him return to international competitions, especially for German museums: we refer to the expansion of the Staatsgalerie of Stuttgart (1977). -1983). Its structure, branded reactionary at the time but appreciated over time, is based on three main figures: a U-shaped block for the museum rooms, an open circular space for the sculpture patio, and an L-shaped piece for the theater. The latter anticipated an extension, implemented several years later, that included a theater arts academy and a music school.

The front area in relation to the main facade is approached in a fragmented and hierarchical manner, responding to the nature of the road in front of it, which resembles a highway rather than an avenue. After ascending to the main stage, we find an entrance hall marked by an undulating glass window and a canopy that symbolizes creativity; All these were painted in various colors contrasting with the earthy colors of the stone plaster.

From the same platform, the first arch emerges, allowing visitors to cross the barrier without entering the museum, but enjoy a spatial experience that culminates in the large circular courtyard of sculptures. For the layout of the exhibition rooms, Stirling chose the model climbing Traditional, treated with an almost classical calm but with sophisticated lighting systems, integrated into the layers.

The most controversial aspects of this extension are the use of classical resources and the juxtaposition between the circle and the square, referencing the Altes Museum in Berlin.

The new Staatsgalerie was one of several museums built in the eighties, a decade focused on the art market during which the Louvre and Tate in London expanded. This proliferation may be related to a counter-reaction to the postulates of the modern movement, which understood these centers as dead entities.

We see a preview of this trend in the Pompidou: the transformation of a closed museum aimed at elites into a multifunctional center for the general public. But its spatial flexibility soon became incompatible with conventional exhibition techniques.

At the opposite end is Hans Hollin's Mönchengladbach's Abdeberg Museum, which breaks into several parts and spreads out over the landscape, offering remarkable variety in the architecture of the rooms. This type of instability applies to many museum projects, and the possibilities range from single buildings to rigid containers, including attempts to establish connections between container and content.

The city of Frankfurt may be the symbol of the decade of the museum: at the end of the seventies a move began to create a dozen centers, many on the banks of the main river (Riverfront of Museums) is the most successful of decorative arts by Richard Mayer, in keeping with its white and primitive grammar, composed of three pronounced cubes forming an L; An element used by the same architect at the MACBA in Barcelona or the Superior Museum of Art in Atlanta, the various exhibition floors are connected by a ramp.

The headquarters of the Menil Collection in Houston (Texas), run by Renzo Piano, is a contrast to his personality. It is based on a series of neutral spaces defined by the quality of natural light; The complex, inspired by Louis Kahn's Gimbel Museum of Art, is built on parallel bays, defined by a structure of steel columns supporting a sophisticated roof, made of long sheets of fiber cement that reflect the sun's rays.

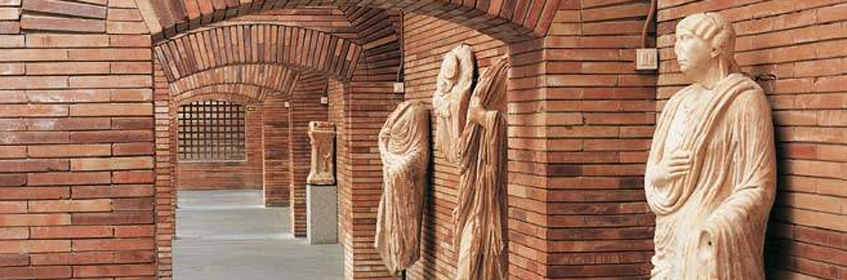

Another position at the Museum of Roman Art in Mérida (1980-1986) was adopted by Rafael Moneo, with the aim of giving architecture a closer relationship with exhibitions. The building, in its typological and formal configuration and its construction system, is inspired by traditional classical and brick-and-mortar Roman constructions: its interior space is reminiscent of basilicas, defined by a series of open arches in parallel walls of exposed brick; In addition, it is illuminated from above by transverse luminaires.

Bibliography

Art history. Contemporary world. Editorial Alliance, 2010.

Alfonso Munoz Cosme. Spaces of Vision: A History of Museum Architecture. Tree, 2007.