Humans have yet to set foot on Mars, but over time, Mars has come to humans. Rocks from Mars, ejected from their home world by processes such as violent impacts, end up traveling through the Solar System — smack! – crashed into the earth.

As we collected these samples of our neighboring planet, a curious pattern emerged. Most of the samples appear to be recently formed rocks on the Red Planet; A peculiarity is that most of Mars is very old.

Age criteria can often be wrong. Different dating techniques have yielded different results, meaning scientists are not entirely confident in their estimates of when these rocks formed on Mars.

A team of scientists from the United States and England has found a way to solve this problem. And, to their surprise, many of these rocks are actually very young — some hundreds of millions of years old. This information can provide clues about how long the meteorites took to get here and about geological processes on Mars.

„We know from certain chemical characteristics that these meteorites definitely came from Mars.” Volcanologist Ben Cohen says of the University of Glasgow who led the research.

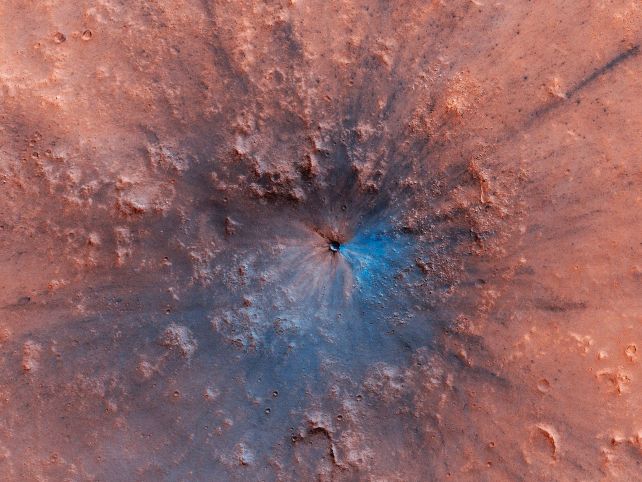

„They were blasted off the Red Planet by massive impact events, creating large craters. But Mars has tens of thousands of impact craters, so we don’t know where the meteorites came from on the planet. For one thing, the best clues you can use to determine their source crater are the age of the samples.”

There are about 360 or so meteorite samples on Earth that have been identified as being of Martian origin. Some 302 of these At the time of writing – therefore, most of them – are classified SercotiteA type of metal-rich Mars formed in the heat of volcanic activity.

Based on how deeply cratered the surface of Mars is, scientists estimate that the surface is very old. If the surface is young and renewed by volcanic activity, many craters are destroyed by volcanic flows. So the rocks from the Martian surface must be old.

Not only are dating techniques for sherkottites here on Earth complicated by their makeup, but what we can glean from them suggests that many are less than 200 million years old. This led to what is known as the Shergottite age paradox Misguided scientists for decades.

Explanations for this surprisingly young possibility ranged from a single point of origin for all younger sherkottites, to the idea that an impact event might have heated and crushed the rock enough to reset its age. But these theories don’t stack up to the evidence—the rocks themselves.

The method used to determine the age of Shergottite is known Argon-Argon Dating, which is based on the decay of radioactive potassium into argon. Because this decay rate produces a known ratio of argon isotopes, scientists can look at that ratio to determine how long radioactive decay has been taking place, and thus the date of a rock sample.

The problem is that here on Earth, we can easily account for different sources of argon and it can become a pattern. For Shergottite, who started on a whole other planet and spent the benefit, who knows how long it will be in space, it’s very complicated. Sherkotite has five possible sources of argon, compared to three for Earth’s rocks.

To compensate, Cohen and his colleagues developed a method to correct argon pollution from Earth and space. „Once we did that, the argon-argon age was young and matched perfectly with other methods like uranium-lead,” He explains.

They dated seven samples of sherkottite to between 161 million and 540 million years ago. Researchers say this may be because frequent bombardment of Mars breaks up the older surface, exposing the younger rock below, filled with volcanic activity. Eventually, that younger rock is more likely to be excavated.

Volcanic activity on Mars may still be ongoing today, and Mars continues to be bombarded. Scientists have evaluated some 200 cases every year Create craters with a diameter of more than 4 meters. So it’s no surprise that younger rocks occasionally hurtle toward Earth, in a circular solar system-y sort of way.

Published in the thesis Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

„Oddany rozwiązywacz problemów. Przyjazny hipsterom praktykant bekonu. Miłośnik kawy. Nieuleczalny introwertyk. Student.