According to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, El Nino is officially here, and it’s a change from the La Nina weather patterns New Zealand has been experiencing for the past three years.

In particular, New Zealand is one of the few countries to experience cooler conditions during El Niño, when the prevailing north-easterly to south-westerly shifts. But what will this El Niño „taste” like?

Time will tell, but El Nino has been around for quite some time. Evidence of its imminent arrival was seen in subsurface ocean temperatures last year, along with the accumulation of warm water in the Coral Sea and western tropical Pacific.

Also, it is outdated. When La Niña finally gave up the ghost in March of this year, global sea surface temperatures were suddenly the highest on record as the tropical Pacific suddenly began to warm (Figure 1 below).

University of Maine, Presented by the author

Meanwhile, higher sea surface temperatures recorded in the tropical North and South Pacific were partly a signature from La Niña and partly a sign of global warming. The resulting „atmospheric rivers” brought heavy rain to California in the north and New Zealand in the south.

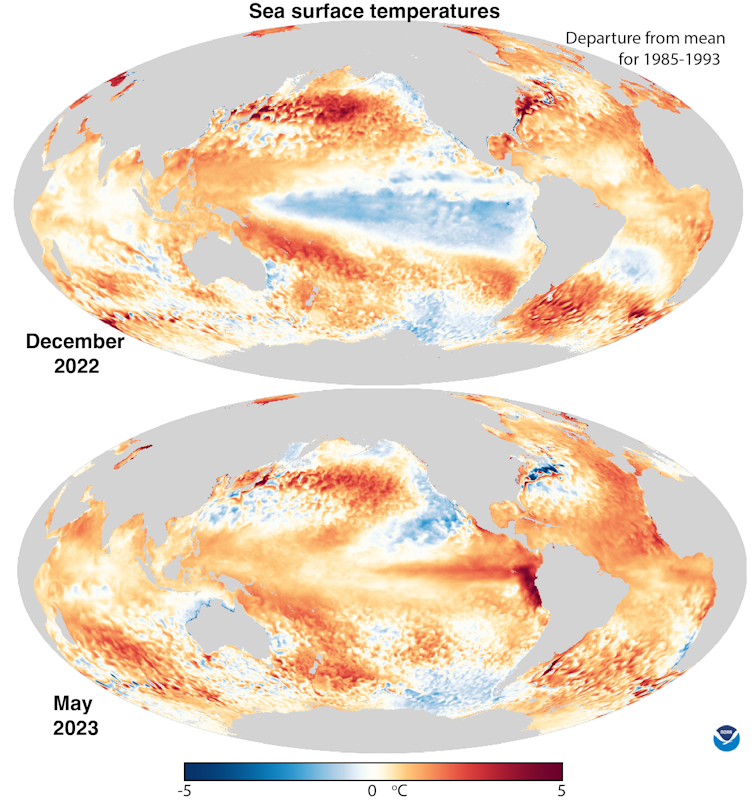

These sea surface temperature changes can be seen immediately by comparing the variations from the mean temperatures for December 2022 and May 2023 (Figure 2 below). We may see a startling change across the central tropical Pacific, with coastal El Niño looking strong off Peru and Ecuador.

Moderate cooling in the eastern North Pacific is associated with a train of storms from Hurricane Ilsa along the US West Coast and northwestern Australia.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Presented by the author

El Nino and New Zealand

However, the weather in the tropics is rarely average. It can be up and down like a roller coaster. In the atmosphere, this is referred to as the Southern Oscillation. The combined atmospheric and oceanic phenomenon is often referred to as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

The bottom of the roller coaster is the cold phase: the cooling of the tropical Pacific, named La Niña, while the top of the roller coaster is El Niño, which occurs every three to seven years. The most intense phase of each event usually lasts half a year.

But El Niños can be very strong and therefore very anomalous. La Niñas, by comparison, are generally moderate in strength and occur more frequently.

El Niños peak in December, although their largest atmospheric impacts do not occur until February. The last major El Niño was in 2016-17, while the weakest El Niño occurred in 2019-20.

Also read: El Nino is back – good news or bad news, depending on where you live

Combined oceans and atmosphere

In the tropical Pacific Ocean, the atmosphere and ocean are strongly coupled. Surface winds drive surface ocean currents, and often affect sea surface temperature distributions, differential sea levels, and so on Heat content of the upper ocean. In turn, the sea surface temperature determines the wind.

Cold water controls atmospheric convection and storm activity, while high sea surface temperatures attract convection, thunderstorms, and tropical cyclones (outside the equator, Earth’s circulation is active).

Heat stored in the tropical western Pacific during La Niña is moved into the atmosphere during El Niño, mainly by evaporation. This cools the ocean and moistens the atmosphere.

Also Read: 2023 hurricane forecast: Prepare for calmer Atlantic, busy Pacific hurricane season than recent years due to El Niño

It changes the main rainfall area. In turn, this changes the latent heat of the atmosphere.”Telecommunications” (links between weather events in different parts of the world) and in both hemispheres – large changes in jet streams and tropical storm tracks across New Zealand, especially in winter.

Because most of the activity occurs in the tropical Pacific Ocean, more settled weather and arid climates often occur over land.

The warmest years in terms of global mean surface temperature are the last stages of El Niño events. Part of a very strong El Niño event, 2016 was the world’s warmest year. But 2023 may break that record — and 2024 will.

So far, there is little evidence that climate change has altered ENSO events themselves. But all of El Niño’s impacts are exacerbated by global warming, including extremes in the hydrologic cycle that include floods and droughts, which are already common with ENSO.

Effects of El Niño

Of course, major El Niño-related events also have serious social and economic impacts. Droughts, floods, heat waves and other changes can severely disrupt agriculture, fisheries, health, energy demand and air quality (mainly from wildfires).

Research shows El Nino „continues to reduce economic growth across the country,” with damage now estimated in the trillions of US dollars.

El Nino is worldwide A major cause of drought; They are especially intense in Australia, Indonesia and Brazil, setting quickly and increasing the risk of wildfires. In the weak 2019-20 El Nino, smoke from fires in eastern Australia affected the Southern Hemisphere enough to block the sun. intensified Subsequent La Niña conditions.

Meanwhile, torrential rains are high, with the risk of flooding especially high in Peru and Ecuador. Very wet conditions can also (though not always) occur in California and the southeastern US.

Also read: New study helps solve 30-year-old puzzle: How does climate change affect El Niño and La Nina?

Another 'Super’ El Niño?

New Zealand had Maximum annual mean surface temperature Recorded in 2022. In the past year, La Nina has bombarded the country with an unprecedented number of tropical and subtropical storms in the Northeast.

A record rain event in Auckland on January 27 and Cyclone Gabriel three weeks later were just two of many such events.

In contrast, New Zealand experiences strong and frequent winds from the southwest in winter and from the west in summer during El Niño. This will promote drier conditions in the east and more rain on the west coast, with generally cooler conditions overall.

But still El Niño varies, and there have been three „super” El Niños: 1982-83, 1997-98 and 2015-16. Whether the latest will join them remains to be seen. But coupled with the cumulative effects of global warming, any El Niño would be very disruptive. We must be vigilant.

. „Gracz. Namiętny pionier w mediach społecznościowych. Wielokrotnie nagradzany miłośnik muzyki. Rozrabiacz”.