Many layers of the earth are hidden from view. But what if we could drill through the planet’s core to the other side? What extreme forces and temperatures will we encounter deep within the planet?

While drilling into the Earth is science fiction, scientists have some ideas about what might happen based on experience with other drilling projects.

Earth’s diameter is 7,926 miles (12,756 kilometers), so drilling across the planet would require an amazing drill and decades of work.

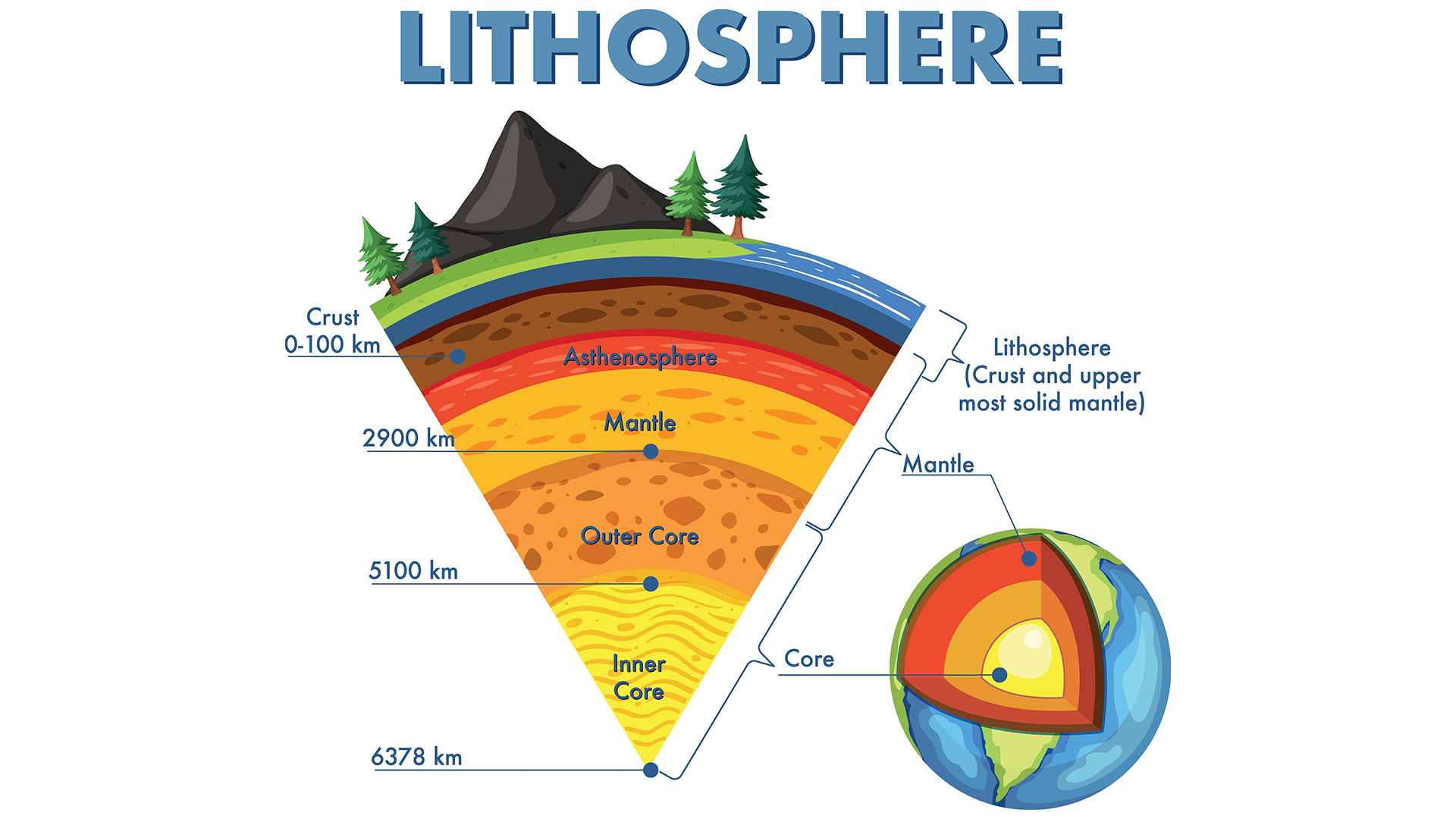

The first layer to drill through is the crust, which is about 60 miles (100 km) thick. US Geological Survey. Atmospheric pressure increases as the drill goes further underground. Every 10 feet (3 meters) of rock is about 1 atmosphere of pressure, the pressure at sea level. Doug Wilson, a research geophysicist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, told Live Science. „It adds up very quickly when you’re talking about a large number of kilometres,” he said.

The deepest man-made borehole today is the Kola Superdeep Borehole in Russia, which is 7.6 miles (12.2 km) deep. At its base, the pressure is 4,000 times that of sea level. It took scientists nearly 20 years to reach this depth World Atlas. That’s another 50 miles (80 km) away, the next layer, the mantle, according to Earth’s layer data USGS. An overcoat 1,740-mile-thick (2,800 km) A layer of dark, dense rock that flows Plate Tectonics.

Related: How many tectonic plates are there on earth?

The boundary between the mantle and the core is called the „Moho” (short for „Mohorovick discontinuity”). Scientists first attempted deep-sea drilling here in the 1950s and 1960s. Project MoholBut they failed.

If we don’t continue to inject drilling fluid into the hole, the hole made in the quest to drill through the planet will stay in the hole. In deep-sea and oil well drilling, the fluid is a mixture of mud containing heavy minerals such as barium. The weight of the fluid equalizes the pressure inside the hole with the pressure of the surrounding rock and prevents the hole from collapsing, Wilson explained.

Drilling fluid serves two additional roles: it cleans the drill bit to prevent sand and gravel from working, and it helps keep the temperature down, although it’s nearly impossible to keep the drill bit cool in the Earth’s inner layers.

For example, mantle temperature is a searing 2,570 degrees Fahrenheit (1,410 degrees Celsius). Stainless steel melts, so the drill must be made of an expensive special alloy such as titanium, Wilson said.

Once through the mantle, the drill finally reaches the Earth’s core about 1,800 miles (2,896 km) down. The outer core is composed mostly of liquid iron and nickel and is very hot, with temperatures ranging from 7,200 to 9,000 F (4,000 to 5,000 C). California Academy of Sciences. Drilling through this hot, molten iron-nickel alloy is particularly difficult.

„It’s going to cause a whole range of problems.” Damon Diggle, professor of geochemistry at the University of Southampton in England, told Live Science. The fiery outer core is like drilling through a fluid, and if cold water isn’t pumped down it will melt the drill bit.

Then, after 3,000 miles (5,000 km), the drill reaches the inner core, where the pressure is so intense that, despite the burning temperatures, the nickel and iron core remains solid. „You’d be under really indescribable pressure,” Teagle said — about 350 gigapascals, or 350 million times atmospheric pressure.

This whole time will be training Pulled down to the center by Earth’s gravity. Gravity at the center of the core is the same as in orbit – effectively weightless. This is because, Wilson said, the pull of the Earth’s mass is equal in all directions.

As the drill continues toward the other side of the planet, the force of gravity will shift to the position of the drill, effectively pulling it „down” back toward the center. The drill must work against gravity as it pushes „up” toward the surface, replacing the downward travel through the outer core, mantle, and crust.

After overcoming all these hurdles, the biggest problem once you reach the middle is that you still have „a long way to go” to get to the other side, Deagle said.

„Oddany rozwiązywacz problemów. Przyjazny hipsterom praktykant bekonu. Miłośnik kawy. Nieuleczalny introwertyk. Student.