Local Representative Violet Yong, A speech The Sarawak State Assembly was told on May 8 about the lack of transparency surrounding the permit application. He asked the state government to create a platform that would strongly inform the public about the applicants and carbon study permit or carbon license holders.

„It is important that this information is made accessible and transparent to avoid mistrust,” he said.

Xin Yang has already held engagements with the local tribal communities of Iman and Long Livok’s Benon tribe, which took place on April 25 and 26. However, residents said they were confused about the scope and impacts of the project but were pressured to sign the documents.

Mudang Duo, a Long Iman villager from the Benan community, said, “Xin Yang intended [of the carbon project] Our forest will have more trees and make the air more fresh. How can this happen?”

He added that under the carbon plan, the Penons are no longer allowed to enter the forest for their daily needs, including cutting wood, hunting and gathering forest products. “This is what Bannon disagrees with us. How can we not enter the forest if we depend on the forest? he said. „We informed Shin Yang that we no longer trust them.”

Contact ban

Local communities have expressed dismay over the Maruti Forest Carbon Project, backed by Samling, another Sarawakian timber company, through its wholly-owned subsidiary, Saracarbon. Saracarbon is the first company to get a carbon exploration permit from the state government in March 2023 and the Marudi project is the first company in the state to be listed on Verra. Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) registration. The project developer estimates that the Marudi project, which consists largely of peatland (69 percent) and lowland dipterocarp forest, will reduce and remove a total of 117,698,804 million tons of CO2e over a 60-year life cycle.

„Despite attending consultation sessions, community members struggled to understand the concepts of carbon trading,” Save Rivers, Keruan and The Borneo Project said in their report.

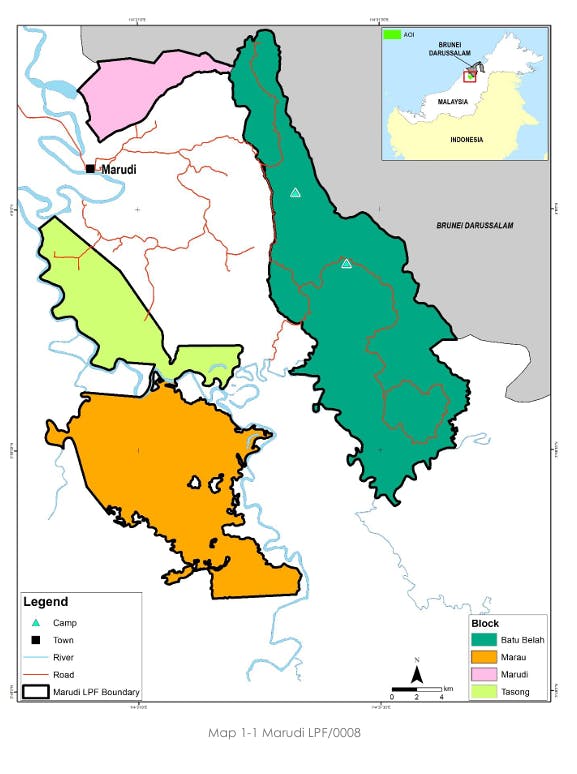

Map of the Maruti Forest Carbon Project area from the draft Maruti Forest Conservation and Restoration Plan submitted to Verra’s Carbon Project Registry. Image: Verified Carbon Standard Registry/ is worse

One of the biggest challenges the company faces is explaining carbon and carbon trading to local communities, said SaraCarbon CEO Laurence Chia, Samling’s CEO. More than 65 percent of people in more than 70 villages around Maruti are below the poverty line, he said, based on a social impact assessment conducted by Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (Unimas), which Sarakarbon engaged as an independent agency to support the project. FPIC procedure.

„Often – and this is completely underrated – how do you go into a village and talk to the most disadvantaged people about carbon? [which is] Intangibles, not something you can see or feel?” Chia said at the Carbon Conference in Kuala Lumpur on Wednesday.

Despite more than a year of continuous engagement as part of the company’s process of obtaining free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) from local people, there are still misconceptions about carbon trading, Saracarbon representatives said.

„In one session, when we were explaining what carbon sequestration is, we were asked if we were going to cut down trees and sell the wood. [as] carbon,” said Fragois Blignant, carbon project leader at SaraCarbon. Then we realized…we had to find different ways to explain that what we do is conservation, not cutting down trees.

A concession given by the State Government to Chamling for the earlier Maruti region assigned For tree plantations that do not overlap with any land owned by local communities or Native Customary Rights (NCR) land, the sia does not fall under the old environmental business. However, if communities have established crops and plantations on non-NCR land, they will automatically be included in the scheme, but will be subject to a land claim process to determine whether the land can legally be used by the communities, the VCS draft notes. The draft also states that local communities will be able to generate additional income through forest conservation activities through the scheme.

End users

The objections listed by the local tribal communities to the Marudi project centered on which party should benefit more from the carbon project’s proceeds and the eventual sale of carbon credits. „[The local residents] If the goal is to protect forests, we hope that communities will receive international funding for forest conservation work against timber companies,” said the Save Rivers, Keruan and Borneo project.

Instead, timber companies that have „exploited the forest for decades” benefit financially, NGOs say. The groups had a contentious relationship with Samling, which sued Save Rivers in 2021 for defamation. The case was later withdrawn amid international pressure.

In his speech, State Rep. Yong questioned how much revenue Sarawak would receive from carbon projects. Under Sarawak’s Forests (Forest Carbon Activity) Regulations Act, the state is entitled to a fee of at least 5 percent of annual carbon credit revenue from forest carbon projects in the state.

„If carbon sequestration is being hailed as a new potential sector to generate income from forest resources in Sarawak, my question is – why is this levy fixed at 5 per cent?” she asked.

Yong pointed out that in Indonesia, the carbon tax rate (CO2e) is 30 rupees per kilogram of carbon dioxide and equivalent. At an index price of 69,600 rupees per tonne of CO2e (tCO2e), the lowest carbon tax rate equates to at least 43 percent of revenue per tonne.

Meanwhile, Zimbabwe’s government has set a target of 2023 30 percent He noted that forest carbon would be imposed on developers for the first decade of any carbon project in the country.

“This is what we need in Sarawak,” Yong said. „It is the desire of the affected communities that every scheme implemented by the government should have a financial benefit sharing scheme with them instead of enriching only a certain elite group.”

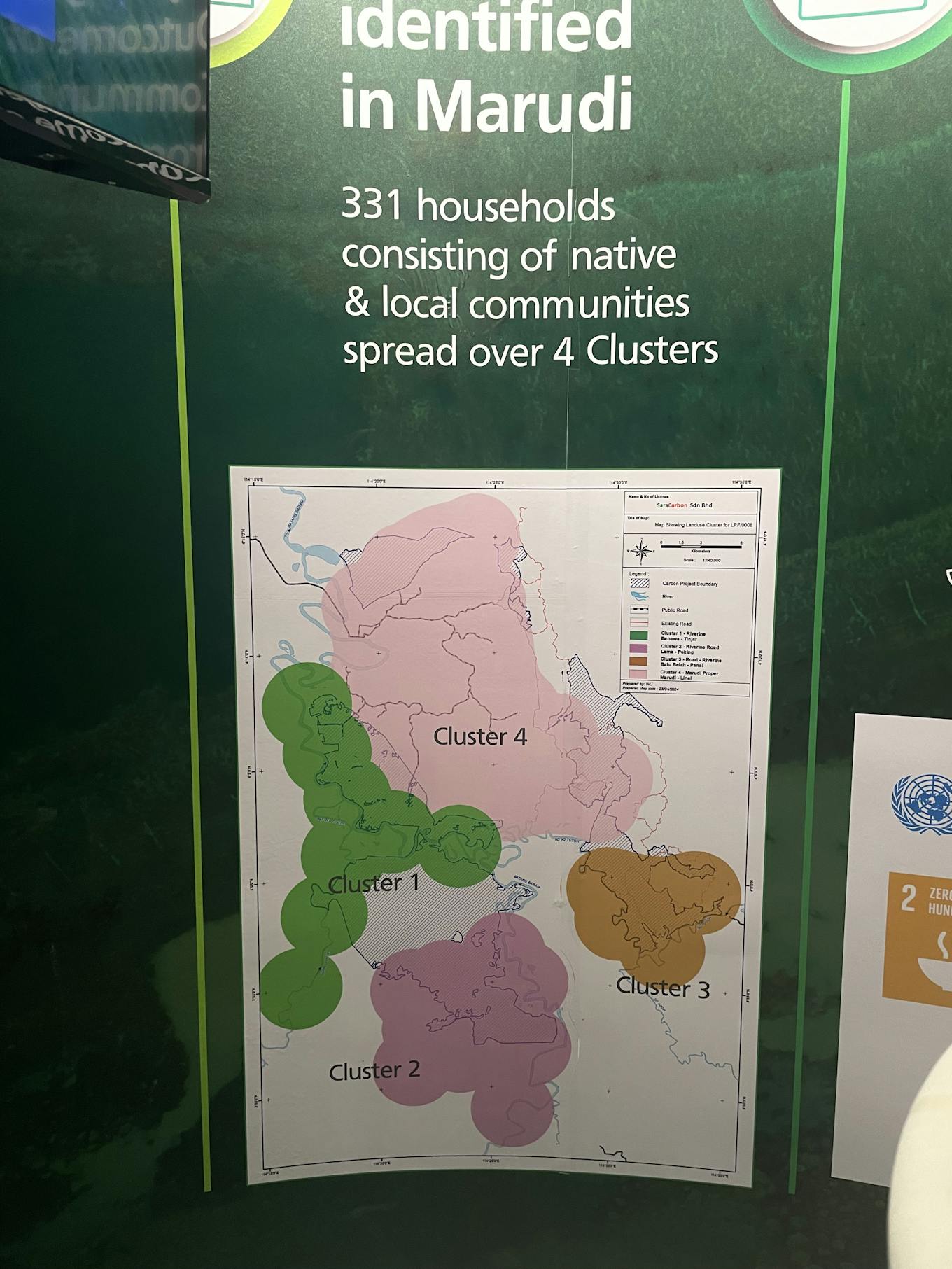

Map showing clusters of villages involved as part of the Maruti Forest Carbon Project. It was showcased at project developer SaraCarbon’s booth at the Argus Asia Carbon Conference 2024. Image: Samantha Ho/Environmental Business

Another Sarawak state assemblyman Baru Bayan also raised similar concerns during the same session. He cited a recent one Report The Union of International Forest Research Organizations for International Forest Governance, which has raised concerns about how much poor communities can expect in revenue generated by carbon projects, has accused unscrupulous actors of exploitation.

„I urge the government to urgently read the report and ensure that processes are in place to ensure that indigenous communities whose lands (or those with claims to such lands) are included as carbon sinks and traded for carbon credits are compensated. What should rightly go to them instead of companies involved in trading activities,” he said.

SaraCarbon’s Chia points out that the government charges a royalty fee of 260 Malaysian ringgit (roughly US$55) per hectare in the carbon project area. „I consider myself being taxed for the good of the people,” he told Ecobusiness. He also noted differences of opinion among local community members that made discussions challenging.

“When we talk about social benefits, they [the locals] We asked, 'How much money are we getting out of this?’ said Xia, pointing to some locals’ demands for payment, but said such practices would not stand up to international scrutiny.

Globally weaker prices for forest-based carbon credits may also be a challenge. Chia pointed out that it will be at least „two years” before credits from the project can be sold, adding that current market prices for nature-based carbon credits are also unfavorable for project developers. SaraCarbon’s costs to develop the project were „at least US$10 tCO2e”, including the high cost of surveying the peatlands, but market prices ranged from US$2 to US$3 per tonne. There are higher price estimates but Xia said, „We haven’t seen it.”

However, Saracarbon is committed to supporting the state government’s objective of promoting forest carbon projects, he said.

. „Gracz. Namiętny pionier w mediach społecznościowych. Wielokrotnie nagradzany miłośnik muzyki. Rozrabiacz”.