NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has zoomed in on one side of the cosmic tug-of-war that has raged between two galaxies for billions of years. Disappointingly, this is a contest in which a clear winner never emerges, as the two galaxies may be joined together at the end of this gravitational contest.

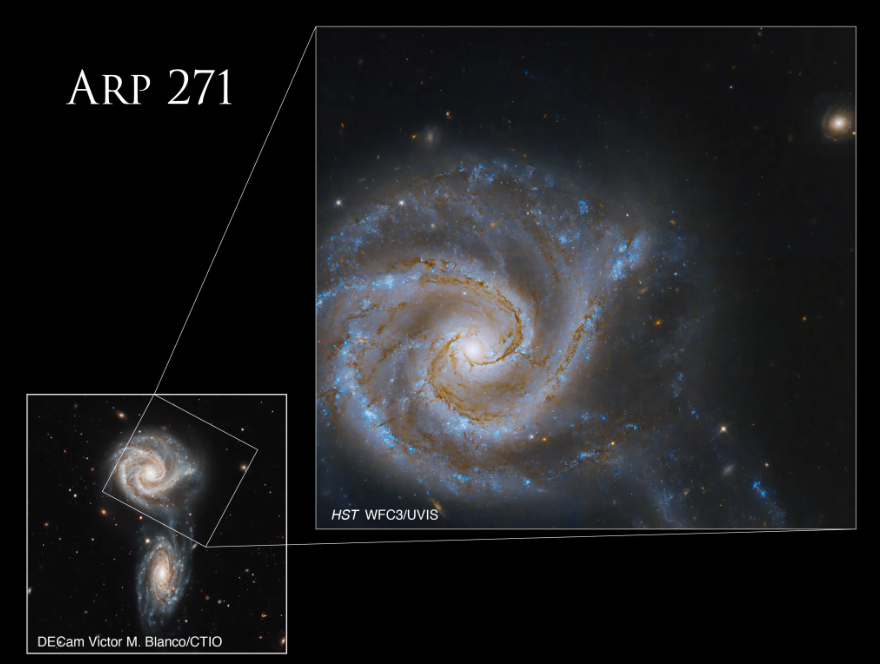

The spiral galaxy imaged by Hubble is NGC 5427. Along with its counterpart, the similarly sized spiral galaxy NGC 5426, the galaxy forms a pair called Arp 271, located 130 million light-years from Earth in the Milky Way.

NGC 5426 is out of frame in this image, and the effects are certainly clear. In the lower right of the spiral galaxy, a trail of gas, dust and stars can be seen moving away from NGC 5427. It results from the gravitational force between two bodies, forming a cosmic rope stretched between them.

Related: Hubble telescope spies massive 'bridge of stars' connecting 2 galaxies in collision (pictured)

Collectively referred to as Orb 271, the two interacting galaxies stretch about 130,000 light-years into space, about 1.3 times the width of our own Milky Way galaxy.

Arp 271 was discovered by British astronomer William Herschel in 1785 and has been studied extensively by several ground- and space-based telescopes, including the Víctor M. Blanco Telescope located at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. Mount Cerro Tololo.

Blanco provided a complete view of this cosmic tug-of-war between these two galaxies, allowing the Hubble image of NGC 5427 to be fully contextualized.

Scientists strongly believe that this interaction will last for many millions of years. What is not yet clear from observations of Arp 271 is that its gravitational interaction will pull these two galaxies together, causing them to collide and merge.

Astronomers can see that gravitational interactions cause gas to be shared between these galaxies, and this in turn triggers the formation of new stars. Many of these baby stars can be found in the cosmic 'rope' of gas and dust that stretches between NGC 5427 and NGC 5426.

Observing interacting galaxies gives scientists a glimpse of what will happen when the Milky Way and its neighboring galaxy Andromeda collide in the future.

The two spiral galaxies are approaching each other at a speed of 671,000 miles per hour (1,079,870 km/h), which is 450 times faster than the top speed of a Lockheed Martin F-16 jet fighter. But they are still 2.5 million light-years away before they meet and merge in 4.5 billion years.

The question is, what will happen to the solar system when this merger occurs?

Scientists simulated a merger between our galaxy and Andromeda in 2006 and found that it could send the Sun and the Solar System flying toward the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*).

After this, depending on how close our star gets to Sgr A*, two things can happen. If our star gets too close to a 4.5 million solar mass supermassive black hole, it could be torn apart by immense gravitational forces.

Alternatively, if the Sun falls into an orbit around Sgr A*, it may spin so fast that it is thrown out of the Milky Way entirely.

By studying interacting galaxies like the one in April 297, scientists can create better simulations that show us whether the Solar System and the Sun will meet a grizzly fate, or a lonely fate where they break away from the universe and wander the universe. Home Constellation.

„Oddany rozwiązywacz problemów. Przyjazny hipsterom praktykant bekonu. Miłośnik kawy. Nieuleczalny introwertyk. Student.