Oregon researchers have revealed how the Columbia River Valley was shaped by the interaction of magma and water, creating its unique cliffs and waterfalls. Their study suggests ongoing geological changes due to subterranean magma activity.

A new study shows that magma and water combined to carve the Columbia River Valley, with magma still influencing its landscape today.

University of Oregon Researchers have added new details to the geological history of the iconic Columbia River Gorge, a vast river valley that cuts through the volcanic peaks of the strata on the border between Oregon and Washington.

Magma and water: forces shaping the valley

In a new study, UO researchers show how magma and water acted as opposing forces to shape this landscape known for its rugged cliffs and stunning waterfalls. Long-term upwelling of magma beneath the Earth's crust bent the river channel and pushed up cliffs and peaks, as the water carved a deep channel between them, the researchers reported in the journal Dec. 20. Scientific advances.

Magma still influences the landscape today.

A deeper understanding of volcanic systems

„A lot of people look at volcanic systems and see volcanoes, sharp cone-shaped things. But actually, volcanoes are the top of a huge network of magma transport,” said Leif Carlstrom, a geologist in the College of Arts and Sciences at the UO. „Here, we see evidence of that deep structure acting on the surface.”

Columbia begins high in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia. After all, it collects water from an area of more than 260,000 square miles and carries it to the Pacific Ocean. It has flowed in some form for billions of years, though not always along the same path.

Credit: University of Oregon

A unique geological phenomenon

„The canyon is this spectacular sight,” said Nate Klema, who led the study as a doctoral student in Carlstrom's lab. „The Columbia is Earth's largest river bisecting a volcanic arc,” a series of volcanoes associated with a subduction zone like the Plateau.

But interpreting it geographically is also tricky.

Klema has spent his life paddling rivers and experiencing firsthand how they shape landscapes. In the new study, he and Carlstrom combined a wide variety of geological and geophysical data collected on the canyon to piece together the story of its origin.

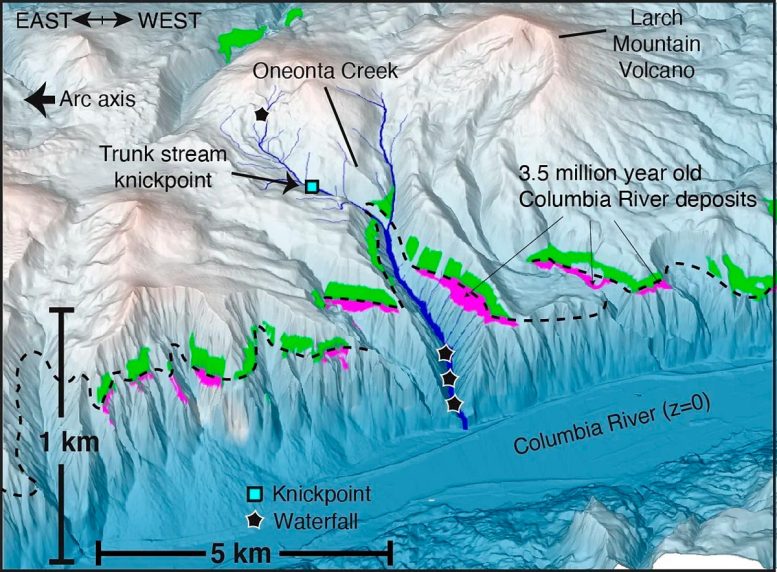

About 3.5 million years ago, a series of volcanic flows changed the course of the lower Columbia River, filling the channel it was moving through and diverting the river northward, where it flows today. Before that diversion, the river channel was essentially flat.

But then, it began to bend, and the magma welling below pushed upward. Uplift combined with the accumulation of rocks from volcanic eruptions helped create the rugged terrain of the valley.

The Columbia River Valley, a magnificent natural wonder on the border between Oregon and Washington, is renowned for its breathtaking scenery. Carved by the Columbia River, the gorge presents a dramatic landscape of steep cliffs, lush forests and a series of waterfalls. This area, rich in both cultural history and geographical significance, stretches for 80 miles and forms part of the Pacific Crest Trail.

The role of magma in development and formation

Carlström, Klema, and their colleagues used a variety of data to show how the movement of magma, more than other tectonic forces, explains uplift.

„One of the striking things after finding this 'strain marker' associated with a now abandoned river channel – the surface of the known initial shape is deformed – all the other data sets correlate well,” Carlström said. „It's unusual to see such a simple yet compelling form that turned out to be such a big decision.”

Measurements of heat escaping from the Earth, as well as maps of the Earth's structure created by seismic waves, both point to magma accumulating beneath the crust beneath the canyon. Other clues, such as the locations of geologically recent vents, provide further evidence that deep magma helped shape the valley.

For example, the team showed how several tributaries flowing into the Columbia from the south side of the valley have steepened in response to magma-driven deformation. They noted places where tributaries suddenly increased their gradient in response to uplift, creating rocky terrain.

Formation of the valley's iconic waterfalls

Those rocks set the stage for the waterfalls the valley is famous for, although other recent events, such as the megafloods of the last ice age, have also shaped the falls.

“What we saw was much bigger than a single waterfall; „With each of these tributaries, the whole river system has to steepen,” said Klema, now a professor at Fort Lewis College in Colorado. „The falls exist because these tributaries have to steepen to get from their headwaters to the Columbia.”

Current influence of magma

The study also shows how magma still shapes the valley and surrounding landscape today.

A pool of molten magma still lies beneath the canyon, with no volcanoes above. As the crust beneath the valley bends, it pushes magma to the sides.

„The layers have been building up for a long time, the volcanoes are stacked on top of the volcanoes because the magma continues to rise up,” Klema said. „One implication is that there will be more volcanoes in the future, more layers on top of existing ones.

Reference: “Magmatic Origin of the Columbia River Gorge, USA,” by Nathaniel Klema, Leif Carlstrom, Charles Cannon, Chengxin Jiang, Jim O'Connor, Ray Wells, and Brandon Schmant, 20 Dec 2023. Scientific advances.

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adj3357

This research was awarded a National Science Foundation Career Award.

„Oddany rozwiązywacz problemów. Przyjazny hipsterom praktykant bekonu. Miłośnik kawy. Nieuleczalny introwertyk. Student.