The creators of Canada’s CHIME radio telescope had no idea what they were doing.

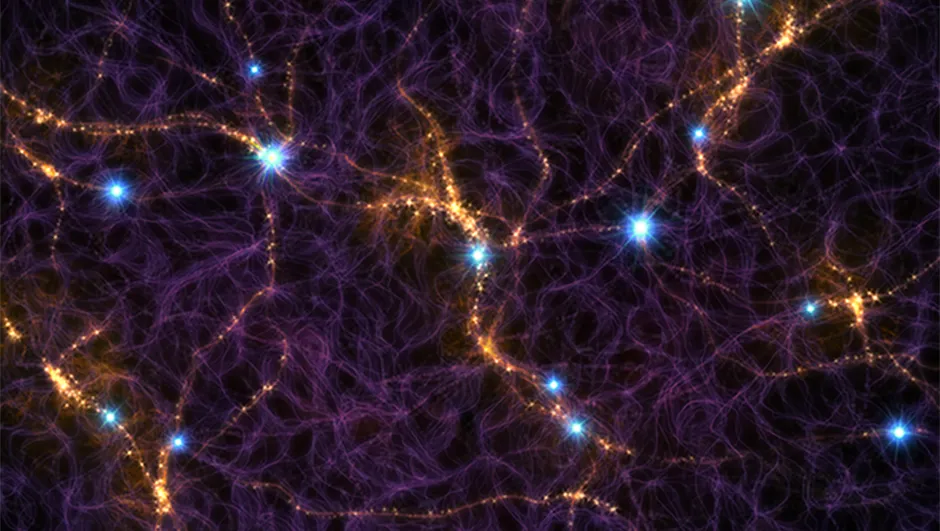

The Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (to give it its full name) is designed to observe large areas of the sky to effectively map hydrogen over a significant portion of the universe.

But it is almost perfectly designed to capture extraordinarily fast bursts of radio waves, known as fast radio bursts.

Fast radio bursts were first discovered in 2007, but between 2015 and 2017, when CHIME was under construction, astronomers looking at archival data realized the events were more common than anyone had expected.

Now CHIME has seen thousands of these explosions – but they remain mysterious.

One of the unusual things is their diversity. Fast radio bursts occur at different frequencies, last from a few milliseconds to a few seconds, and while some repeat, others do not.

CHIME saw precisely one fast radio burst that appeared to come from the Milky Way, but others appeared to originate in galaxies billions of light-years away.

With a rapidly growing list of such materials (and hydrogen is still on the map), the CHIME team is busy.

But others are now poring over the telescope’s rich datasets, and a joint study by astronomers in China and Australia has found something interesting in CHIME’s collection of persistent fast radio bursts.

Gravitational lensing

The team set out to test an old idea: that fast radio bursts could be affected by gravitational lensing.

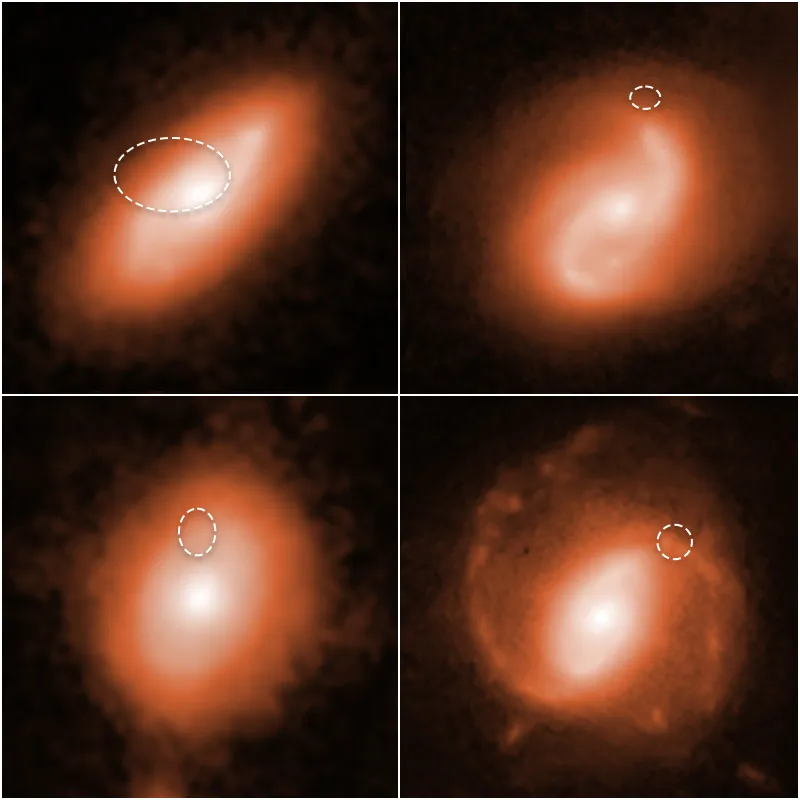

Lensing is the process by which light is bent by gravity, which you may have seen in images of collapsed galaxies from the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope.

In general, light from a distant galaxy is bent by passing close to a nearby galaxy or cluster, but smaller, more massive objects—passing black holes or free-floating planets—can also cause a lensing effect.

Such 'microlensing’ brightens a background source, but it can cause a delay in the light reaching Earth, although how long such a delay lasts depends on the situation.

Different paths around the lens take different times, so instead of seeing one fast radio burst, we get multiple radio waves from the same burst.

The team used a machine learning technique to check for similarities between different bursts from the same continuous fast radio burst.

Rather than truly repeating—whatever causes these events is difficult to interpret as more powerful and destructive—lensing turns an explosion into something we see more than once.

They analyzed 42 fast radio bursts and found that 2019 may be a lens.

Its bursts were similar enough to seem suspicious, although they were not identical—presumably due to deviations from their paths around the lensing object.

More observations and more radio bursts are needed before anyone can believe this conclusion. The similarity between lensing is a red herring and bursts are a coincidence.

Fortunately, CHIME is still scanning the sky, and another explosion will occur in about a minute.

Chris Lindott was studying A candidate lensed FRB in the first CHIME/FRB catalog and its possible implications Chenming Chang et al. Read it online: arxiv.org/abs/2406.19654

„Oddany rozwiązywacz problemów. Przyjazny hipsterom praktykant bekonu. Miłośnik kawy. Nieuleczalny introwertyk. Student.